Computing technology, and technology in general, has met a sudden and ubiquitous growth,

especially during the course of the 21st century and has transformed society in several aspects of everyday life.

Tech-industry job postings have grown by 15% between 2021 and 2022, while the general job postings in other

fields dropped by 13%, only a few tech-related specialisations present a surplus in skill, and the tech-related

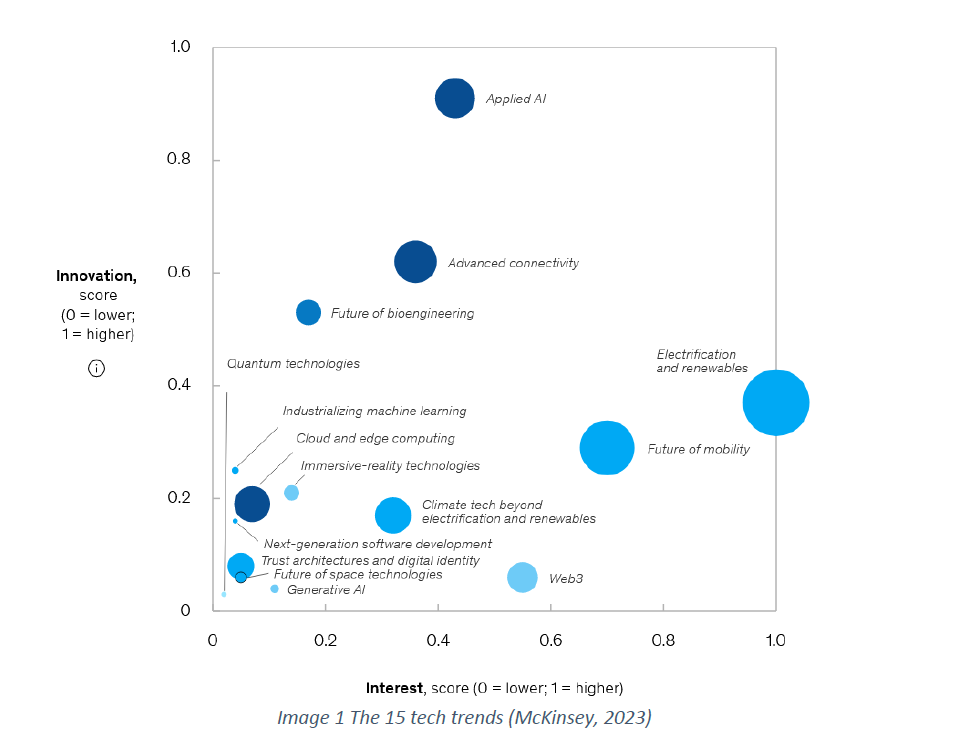

investments reached a combined value of 1 trillion US dollars in 2022 (McKinsey, 2023). The so-called AI revolution

further draws the picture regarding the advancement of computing technology, with applied AI being considered

one of the most innovative technologies (doubling the innovation metrics from 2018 to 2022) with sufficient

interest in the global market, increase in the global picture of AI adoption, budget allocation and the relation

between cost and revenue of AI applications (McKinsey, 2022).

Similarly to every other revolutionary technology, such as the technologies developed during the three industrial revolutions, computing technology not only brings a plethora of benefits but also raises significant ethical concerns. As an analogy, ethical concerns have also been raised during other Industrial Revolutions, for example, the ethics of craftsmanship concerning the 1st Industrial Revolution (Freeman, 1923) and the unequal distribution of wealth during the 2nd Industrial Revolution (Engelman, N.D.).

Ethics in computing contain a broad spectrum of considerations – from the professional responsibility of developers and engineers to the societal implications of deploying AI and data technologies, including the different approaches of ethics, such as normative and applied ethics (Stahl et al., 2016). As computing professionals and with the technological tools penetrating everyday life, understanding, evaluating and addressing ethical concerns is paramount to ensure no harm to society.

In this paper, we will address ethical considerations in the form of a case study, assuming that we are computing professionals conducting data-related work for a company named companyA, which conducts individual assessments regarding the protection situation of individuals in perilous situations on behalf of humanitarian organisations. The assessments involve individual interviews, personal data and sensitive data collection such as addresses, specific needs and medical conditions, and socioeconomic situation.

Our work involves people at risk, collecting and analysing sensitive information, and is subject to several ethical and legal concerns. At their core, ethics refer to the principle of right and wrong and related choices of individuals that guide their behaviours. Considering the different realms of ethics, the principle of right and wrong can be based on the theory of consequentialism (the ethical value of an action is judged based on its consequences), deontology (the ethical value depends on the intentions of the actor) and virtue ethics (the ethical value depends on the overall character of the actor), among several other theories (Stahl et al., 2016). In our example, the ethical concerns will be judged based on the professional bodies that dictate the code of conduct of computing professionals, related professional practice, and relevant legislation.

Specifically in computing, ethics concentrate on what can potentially harm individuals or communities. The humanitarian principle of do not harm (UNHCR, 2019) is a generic and not computing-specific principle that every humanitarian professional should abide by and, considering our specific work, directly applies to us. In regards to our interviewing exercise, several ethical concerns can be raised, with one of the most important being balancing the equities between the right of the data subject and the overall benefit of the population of concern. For example, during the data collection process, individuals may refuse to answer specific questions about their specific needs, thus distorting the subsequent analysis. This refusal will skew the analysis results, which, as a consequence, may fail to provide value to the interviewed population. Although the subsequent actions of the interviewer may be seen as a complex ethical concern, the data subject's right to refuse to answer specific questions or withdraw from research remains irrevocable, according to both professional research practices (Yale, N.D.) and humanitarian practices, which consider consent as an ongoing process (UNHCR, 2018).

Additionally, during the data analysis, we may notice interviewees with severe protection concerns and have the dilemma of taking action to attempt to assist them. Despite this being a natural human reaction, the individual's data protection should come first, especially considering their situation. Regularly, in protection-related interviews, the interviewees are asked if they would like to receive referrals for services that may assist them with their specific needs. The presence of a social worker during those interviews is also of great importance, and the data analyst should be aware of their roles, responsibilities and lack of specific training; thus, they should refrain from such actions, which may put individuals in more significant harm. In this instance, we can directly connect this ethical concern with deontology, where it becomes evident that the actor's intention is not important; instead, the consequences are more significant, as described in consequentialism.

Finally, considering that such research may be psychologically traumatising for the researcher, measures should be put in place to ensure that the researcher does not face any ethical dilemmas regarding altering the spirit of the research outcome, either by overly highlighting the negative aspects of the report to affect decision-making or promote the positive aspects of the report to overly highlight human-suffering (University of Cambridge, N.D.). As mitigation measures, psychosocial support should be available throughout and immediately following the research (Researcher Mental Health Observatory, 2021), ensure that the work is peer-reviewed by a third party (ACM, 2018), and have a sound predefined research methodology (Kelley et al., 2003).

In conclusion, ethics shall be in the main picture of computing and not be considered a secondary duty. With technology continuing to evolve, ethical dilemmas are expected to become more complex, as can also be seen through the increased ethical concerns of every subsequent industrial revolution. Concerning data-related computing ethics and the involvement of people with specific needs in humanitarian contexts, addressing such challenges requires organisations and professionals to think outside of silos, and it needs a collective effort that involves ethicists, humanitarians, policymakers, computing and data professionals as well as the population of concern. It is only through dialogue, public consultation, strict oversight and enforcement, professionalism and commitment to upholding the ethical principles that we can ensure that the third and fourth industrial revolutions will not be overshadowed by harm to society and that humanity will thrive and enjoy the benefits of the innovation and prosperity that computing has to offer.

ACM. (2018) ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct. Available from: https://www.acm.org/code-of-ethics [Accessed 15 October 2023 2023].

Engelman, R. (N.D.) The Second Industrial Revolution, 1870-1914. Available from: https://ushistoryscene.com/article/second-industrial-revolution/ [Accessed 10 October 2023].

Freeman, A. (1923) Some Ethical Consequences of the Industrial Revolution. The International Journal of Ethics 33(4): 347-444. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1086/intejethi.33.4.2377592

Kelley, K., Clark, B., Brown, V. & Sitzia, J. (2003) Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 15(3): 261–266. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzg031

McKinsey. (2023) McKinsey Technology Trends Outlook 2023. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-top-trends-in-tech#tech-talent-dynamics [Accessed 10 September 2023].

McKinsey. (2022) The state of AI in 2022—and a half decade in review. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai-in-2022-and-a-half-decade-in-review [Accessed 13 September 2023].

Researcher Mental Health Observatory. (2021) Researcher Mental Health and Well-being Manifesto. Available from: https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/department-dam/D-GESS%20DAM%20General/Dokumente/wide/MentalHealth/Researcher%20Mental%20Health%20Manifesto.pdf [Accessed 14 October 2023].

Stahl, B., Timmermans J. & Mittelstadt B. (2016) The ethics of computing: A survey of the computing-oriented literature. ACM Comput. Surv. 48(4): 1-38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2871196

UNHCR. (2019) Humanitarian Principles. Available from: https://emergency.unhcr.org/protection/protection-principles/humanitarian-principles [Accessed 13 October 2023].

UNHCR. (2018) UNHCR STANDARDISED EXPANDED NUTRITION SURVEY (SENS) GUIDELINES FOR REFUGEE POPULATIONS. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/sens/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2020/09/UNHCR_SENS_Pre-Module_v3.pdf [Accessed 15 October 2023].

University of Cambridge. (N.D.) Good Research Practice. Available from: https://www.research-integrity.admin.cam.ac.uk/good-research-practice [Accessed 2 October 2023].

Yale. (N.D.) Rights as a Research Participant. Available from: https://your.yale.edu/research-support/human-research/research-participants/rights-research-participant [Accessed 15 October 2023].